The French Dispatch by Wes Anderson

A personal overview of its contents and a delve into its aesthetics.

‘The French Dispatch’ is a film directed by Wes Anderson.

Its creation represents a nostalgic love letter to journalism, artistry, & the intersections of that creativity. It is a movie that celebrates stories by celebrating the wonderful individuals who share them. The film is separated into 5 sections, imitating the format of a publication magazine. Personally, I love this movie because of its stunning cinematography and the fresh breath of life that is found within every single story told within the film – no two stories are the same, and each have an array of meaningful truths to acknowledge.

The film is all about collecting stories and spinning them into something delightful, charming, and light (even when they involve dark and heavy elements).

I feel that this in-film magazine is proof of the vitality of creative expression and the importance in a distribution of stories. The French Dispatch magazine and its high demand represents humanity’s need for culture; a need to find a connection to places bigger than themselves.

I recognise this yearning to learn more about the world around us and their narratives, within myself. I know firsthand how hungry a person gets for increased exposure to unfamiliar things. Us humans thrive on growth and knowledge, and when shown a sliver of anything new, we latch onto it because it is in our nature to be inquisitive and curious.

This issue of The French Dispatch magazine introduces the world to a collection of individuals whose lives are interconnected in personal ways. It is an introduction of stories held within the fictitious city of Ennui-sur-blasé (which translates to “boredom-on-apathy”). Selecting this direct French translation to represent the fictional city Anderson had created, is an interesting juxtaposition to the overall theme of the film: To procure appreciation and interest in journalism.

The word Ennui is largely associated with boredom, a lack of interest, while blasé means to be indifferent, apathetic. It’s an interesting choice to give this fictitious metropolis such a name, especially when the main characters are an antitheses of any kind of insipidity. Yet, the city’s title perfectly alludes to the mundane lifestyle of its everyday citizens.

It was an intentional decision on Anderson’s part to further highlight the French Dispatch’s distinct ability to bring life and poetry into this town whom at-first-glance, is unassumingly disinteresting. The elevation and journalistic spin of these stories distract from the general disinterest that permeates Ennui. The French Dispatch is no longer just a magazine, it is a study of all kinds of people that live in Ennui and it forms a connection between individuals from diversifying walks of life. Ennui becomes a bond that can be shared between humans with different stories.

‘The Cycling Reporter’ is a section in the magazine posing as a small travel guide for the fictitious city of Ennui — created for the sole purpose of introducing the individuals that reside there. I love this section because it turns something as mundane as public transportation, laundry, or feline encounters, and creates an artistic narrative on its existence. This travel guide revitalises the history of Ennui while also appreciating the daily normalcies of its modern-day life. It is a study of all kinds of people that live in Ennui and it forms a connection between all these individuals who come from different walks of life.

“In the Flop Quarter: students. Hungry, restless, reckless... In the Hovel District: old people. Old people who have failed.”

Ennui becomes a bond that can be shared between humans with different stories. Such journalistic flair, can turn brooding evenings with danger lurking around any corner, into something with beauty.

“As the sun sets, a medley of unregistered streetwalkers and gigolos replaces the day’s delivery boys and shopkeepers, and an air of promiscuous calm saturates the hour. What sounds will punctuate the night, and what mysteries will they foretell?”

I feel that this section of the magazine is such an astute example on Anderson’s motive for producing this movie. It showcases the beauty of journalism through how it cultivates history and currency, poetically.

The third section of the magazine is one of my favourites. A story of love, and a recollection of artistry, might be the best way to describe ‘The Concrete Masterpiece’. And although this is all it may seem like at the surface, this section of the magazine also explores the effects of incarceration on tortured individuals; friendship; and the beauty of belief within new forms of creativity.

I think the most important aspect of the start of this section of the film, is the highlighted effect incarceration has on mentally unstable individuals who require guidance and support. Evidence of its pivotal nature is seen during Rosenthaler’s speech:

“I’ve been here 3647 days and nights. Another 14,603 to go. I drink fourteen pints of mouthwash-rations per week. At that rate, I’m going to poison myself to death before I ever see the world again, which makes me feel — very sad. I’ve got to change my program. I’ve got to go in a new direction. Anything I can do to keep my hands busy: I’m going to do it. Otherwise, I think maybe it’s going to be a suicide.”

Such raw honesty and admission to wanting to change his routine in order to save his life — to save it from himself, sparks so much sorrow and sympathy within myself when I first heard it.

It proves that most often than not, the facilities built to hold the mentally tortured, are not as effective as we think. Sadly, our reality is not so different to Rosenthaler’s account of his experience in detainment facilities. Justice and incarcerations systems around the globe should invest more time into ensuring a strong support and guidance system is in place for these tortured individuals; instead of leaving them to their self-destructive tendencies.

Rosenthaler’s account on love and his outlook on life instill a curious and appreciative nature within myself for the bizarre; implementing the understanding that things are not always as simple as they seem. There is beauty in terror and violence in companionship. Humans hold a multitude of layers in their depths.

The next two seections which are titled ‘Revisions to a Manifesto’ & ‘The Private Dining Room of The Police Commissioner’, are other favourites of mine. ‘Revisions to a Manifesto’ covers themes like interpersonal connections; love in varying forms; loneliness in creative pursuits; and the consequences of industrialisation on the youths of today’s world.

I think the political rhetoric of this story is the most crucial takeaway point, as it gives an honest portrayal of teenagers and their bustling desire to fix the constitutional climate, built by the generation before them. The story ultimately concludes with the fact that having this responsibility on any youth’s shoulders can result to negative circumstances for their wellbeing. It can bring external danger as well as mental distress onto these teens.

It has taken Zeffirelli’s teen-hood for him, pushing him to center a political movement at such a young age. This destructivity can also be portrayed through a suicide scene of an individual whose responsibilities lie at the opposite spectrum of Zeffirelli's activism.

Morisot is a soldier serving his National Duty-obligation in the Mustard region. He fights on behalf of an imperialist army in an unjust war of totalitarian aggression against his own choice. The movie shows him sliding out a five-storey window before falling to his ultimate death. Prior to his passing, he’d told the rest of the soldiers that his dream was to be a protester. When asked why, he had replied, “I can no longer envision myself as a grown-up man in our parents’ world.”

Such an occurrence is devastatingly traumatic to have seen and I can’t imagine how every character in the scene must have felt after his death. To see how much the reality of the world negatively affects the emotional and mental state of a teen (who still had so much potential left in his life), leaves me to wonder: How does the state of society around us, negatively affect our growth and wellbeing? How much pressure lies on the shoulders of youths in real-life?

Perhaps the answer isn’t so different from the truths presented in this movie.

However, I think that the only thing I disagree with in this feature, is that journalist Lucinda Krementz is destined to a lone, spectating life. I feel like the end of this piece portrays Krementz as someone who is better off behind the typewriter — writing about another life rather than trying to live her own. We have been shown that she’s capable of attracting love and interest in other people — there’s no reason why she should hold herself back, just because her and Zeffirelli’s love story came to an end.

While Zeffirelli appreciated Krementz’s intimacy, his ultimate love lied in his freedom and his chances at newer experiences. He was always bound to stay solely as another subject in Krementz’s stories, cemented as a teen in unrest over the patriarchal climate of Ennui. But that doesn’t mean Krementz failed at being loved. I feel that she simply has to try again. Which makes me realise I should also uphold myself to this standard I so desperately want to apply on Krementz. I shouldn’t allow the outcome of my relationships to determine my self-worth.

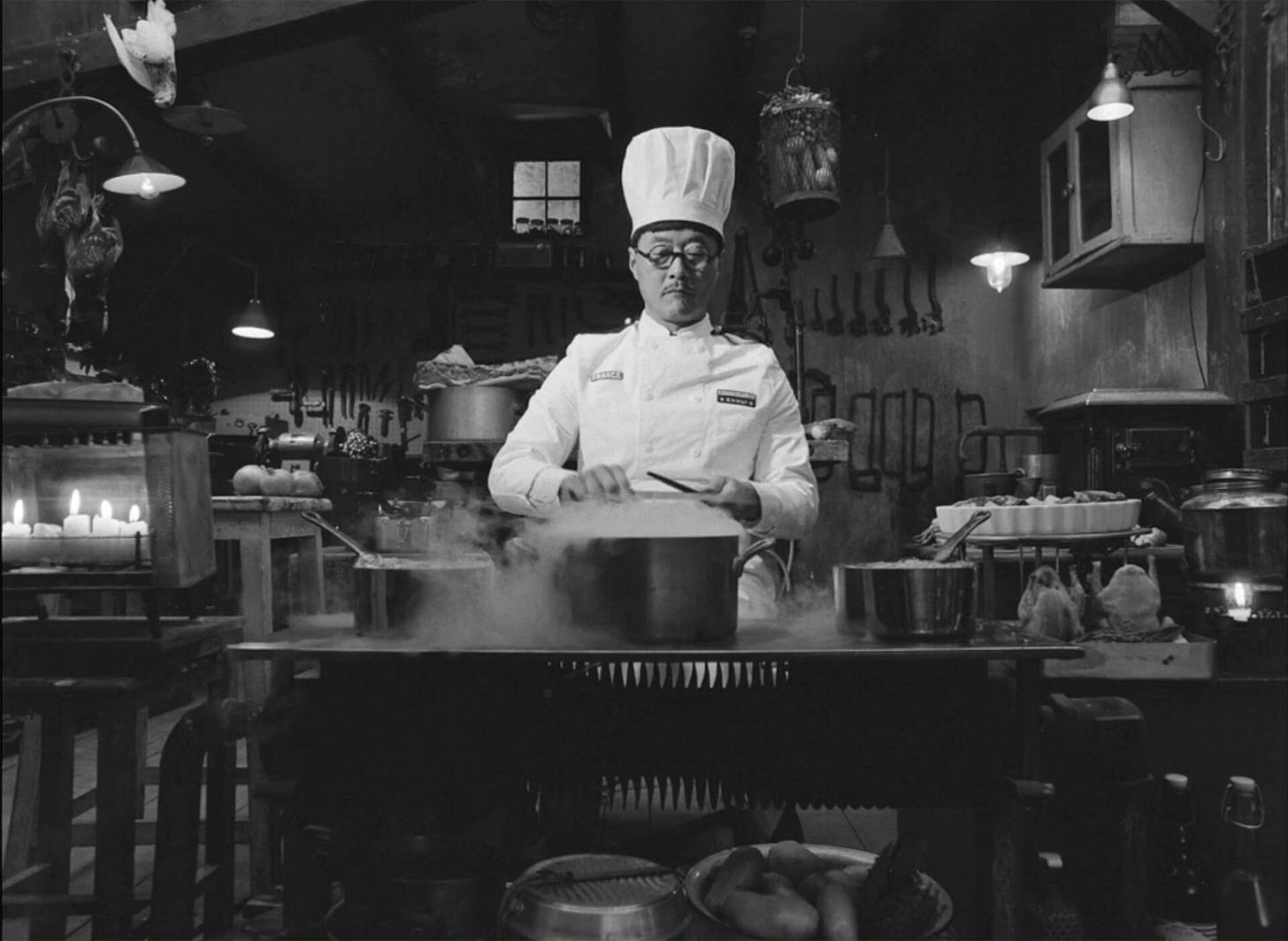

‘The Private Dining Room of The Police Commissioner’ is a piece that divulges the strength of love: Love found in food; love of a parent; the love in a person’s heritage. What I personally consider the most fruitful message from this story, is the admission of the harsh realities faced by (even the most successful) foreigners, in a predominantly white country. I’ve never seen a piece of western media acknowledge the struggle foreigners face to consistently push themselves to their limit — because we are only acknowledged if we are great.

The expectations of greatness set for us because of our heritage, almost constantly feels like a rite of passage we’re obligated to achieve in order to stay in this new land. This statement can be supported by something character Nescaffier had said when he was sent to help re-obtain the Commissaire’s son from the hostage situation. In order to do this, he had to cook for the kidnappers and lace their food with poison, inevitably poisoning himself in the process.

During his recovery, he was told his ‘bravery’ was admired, to which he responded,

“I’m not brave. I just wasn’t in the mood to be a disappointment to everybody. (in explanation:) I’m a foreigner, you know.”

Roebuck Wright shares this struggle with Nescaffier as a black, gay, intellect; at a time in America where there's not a lot of room for that. They are both running from scrutiny because of how unbelonging they feel in this new place. And yet, it almost seems like it would be no different for them in the place of their heritage.

“Seeking something missing. Missing something left behind.”, Nescaffier had said.

“Maybe, with good luck, we’ll find what eluded us in the places we once called home.”

I definitely appreciate and love this section of the in-film magazine because it's a nod to individuals whose lives have been fractured across continents. Hopefully one day, people alike to Nescaffier and Wright will be able to find their place in society without constantly needing to prove themselves to external parties. Nescaffier and Wright, both possess such crucial abilities to contribute to society, and I feel that this story in the film properly highlights and appreciates them for this.

Not only does this ensemble point out the magnifying force of love in food or amongst people, but it also highlights love's slow bloom within your own self — Wright and Nescaffier’s talents are crucial aspects of their character. Yet despite this greatness, I see Wright and Nescaffier as individuals who are detached and systematic, almost robotic in the sense they’ve turned their talents into a driving force in which they present themselves to the world. This ties in with my previous statements in the paragraph above.

Near the end of this visual piece, I feel that we see Nescaffier and Wright use these abilities to more personal fulfillments; in order to find comfort within their own skin whilst navigating wider society. Love found in literature and food helped these two men find love within themselves. This movie made me realise that Nescffier and Wright were constantly externalising love to their creations, and it was time they started internalising that love for themselves. I believe I can learn to do this for myself as well, and stop allowing society to come in the way of my self-love.

The world cannot appreciate myself the way I’m able to, and I should stop breaking my own back to achieve the approval of people incapable of that.

‘The French Dispatch’ and its aesthetics

Wes Anderson stays true to a collocation throughout the film; attaining an idealistic and veristic nature for this cinematic universe. While many of the film’s plotlines diverge into a darker, more pragmatic tone, its palette and colour-grading exudes a lucidity that would be found in a transient state of sleep.

‘The French Dispatch’ is Anderson’s tenth feature film, and audiences can confidently recognise his distinct mastery in construction; all of which entail a deeply considered attention to his set design, cinematography and performance while staying true to his meticulous aesthetic.

It’s no secret Anderson’s films stay true to traditional theatre; a statement which can be backed by the conduct of his actors. Their performances are uncanny to having a playwright script narrated to life. It has been said the primary inspiration for The French Dispatch magazine resides in The New Yorker, a similarly structured lifestyle magazine. Anderson’s immense love for The New Yorker has driven the creation of the film’s essence and its contents — all of which have been dramaticised from real events reported in The New Yorker.

Javi Aznarez is the official illustrator for the mock magazine covers of the in-film publishing company. As seen from the two images above, it’s clear just how much inspiration was taken from The New Yorker and its nature.

A single distinctive factor that separates The French Dispatch from its muse however, is its stylised, and cartoonist illustration — that of which exaltis a fresh air of playfulness. This allows me to revert to one of my initial statements touching on how Anderson has achieved a state of airiness. The heavy elements in each feature within the film are balanced with the ingenuity of his artistry.

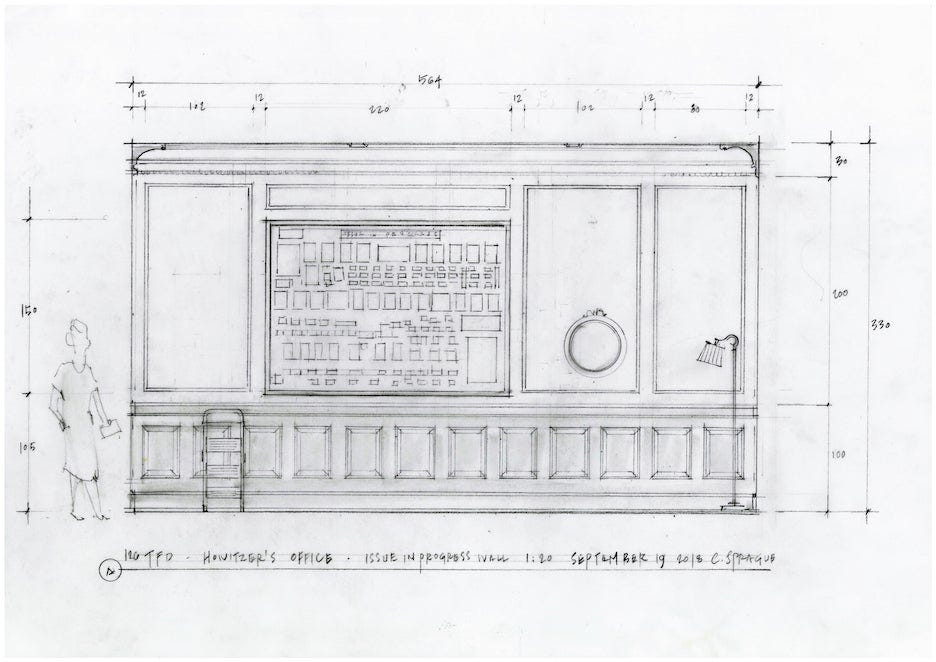

This creative vision bleeds into the composition within shots throughout the film. Anderson’s artistic directory would not have enabled the ‘French Dispatch’ to have achieved its distinctive personality or charm to a satisfactory extent. Set-design fully enunciated Ennui’s presence and speciality.

The Hollywood Reporter released an article concurring with the same notion.

Production designer Adam Stockhausen fell into a slight panic at the start of filming due to the diverse nature of each feature and their locations. Each story resides in largely differing localities within Ennui, producing a large range of environments to design for — albeit the fact that everything occurs in the same city. The only thing holding these locations together is the fact that their stories are told through The French Dispatch.

Stockhausen agrees that ‘The Cycling Reporter’, was a great piece to start with as a prologue of sorts, “It was a great place to start,” he said, “because all the stories connected through the town.” It emphasises just how much Anderson prioritised the inter-connectivity between each feature whilst still maintaining their individualism through the differing sets and locations.

A full interview was held with Stockhausen by The Wrap.

To conclude this overview, its been established the Anderson’s directory holds phenomenal care and construction; explaining why artists and viewers alike hold his works in high regard. The distinction between this feature film and Anderson’s other works, is that I value the diversity in which all stories told within the movie are given their own space to breathe and come to life — allowing their natures to never stray into any form of conformance.

The film is cognisant in the fluidity and ephemeral nature of life while also appreciating it for the love and beauty it can possess.